Laundry pods and laundry sheets are often marketed as eco-friendly alternatives to liquid detergents because they don’t come in big plastic jugs. As a result, many people believe that these products are plastic-free. Several brands state loudly, and incorrectly, that they contain “zero plastic” while also listing PVA as an ingredient. We aim to clear things up: laundry pods and laundry sheets that list PVA, PVOH, or polyvinyl alcohol as an ingredient contain plastic.

What is PVA?

PVA, also known as polyvinyl alcohol or PVOH, is a dissolvable plastic used in many applications including laundry sheets and dishwasher pods. Most people recognize the thin plastic film used in pods as plastic, but some may not realize that PVA is also used to make dissolvable laundry sheets and strips.

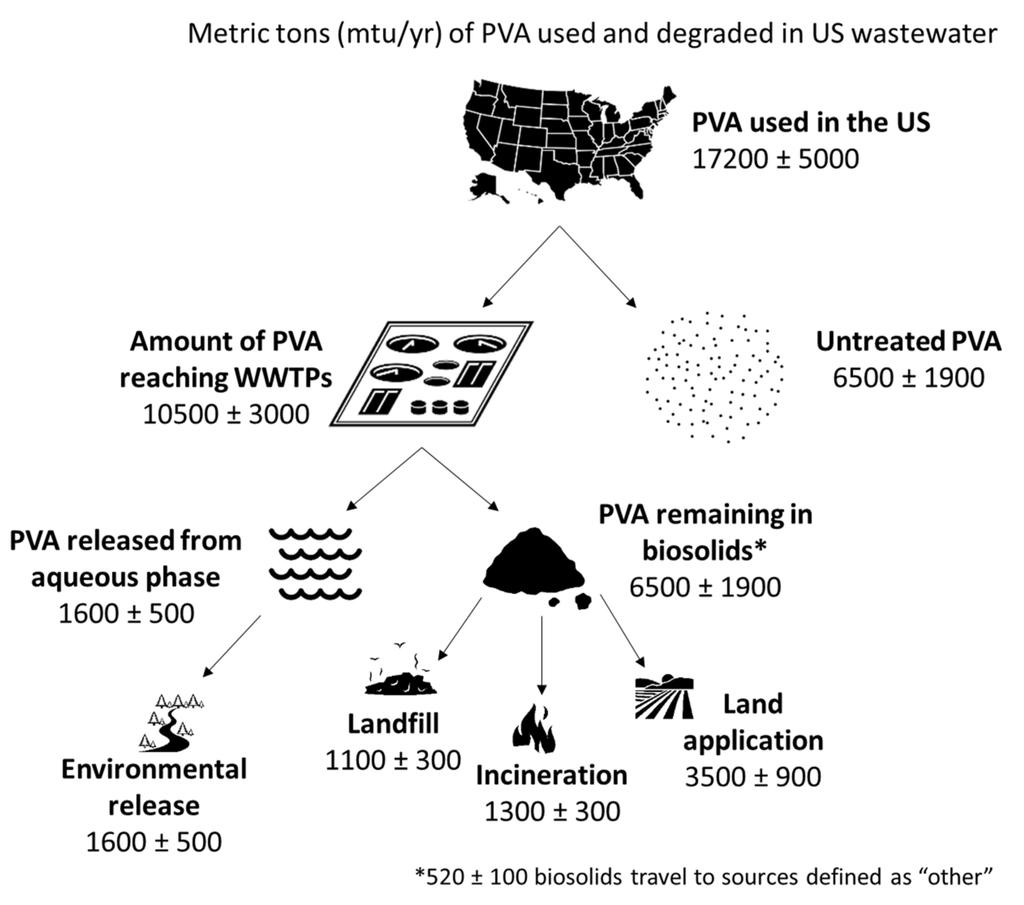

The United States uses about 17,000 metric tons (over 37 million pounds) of polyvinyl alcohol annually!

What cleaning products contain PVA?

Laundry detergent, cleaning products, and soap can all be made with PVA. If the cleaner comes in a dissolvable sheet or wrapped in a dissolvable film, check the ingredient list for polyvinyl alcohol, PVA, or PVOH.

Here are some examples of products that contain PVA:

- Laundry detergent sheets

- Laundry detergent strips

- Laundry detergent pods

- Dissolving fabric softener sheets and strips

- Dishwasher pods

- Hand soap pods

- Hand soap sheets

- Body wash sheets

- Toilet cleaner pods

- Toilet cleaner sheets

- All-purpose cleaner pods

- All-purpose cleaner sheets

- Dishwasher cleaner pods

- Washing machine cleaner pods

Both detergent pods and laundry sheets contain PVA

Is PVA bad for the environment?

PVA used in laundry pods and sheets is designed specifically to dissolve plastic into the water system. A study published in 2021, Polyvinyl Alcohol in US Wastewater Treatment Plants and Subsequent Nationwide Emission Estimate, concluded that the PVA used for these products does not readily biodegrade during wastewater treatment and is eventually released into the environment. It is a comparable issue to the use of microbeads in cosmetics or the release of microplastics from clothing made with synthetic materials.

PVA is sometimes marketed as an environmentally-friendly material because it allows detergents to be encased in a small amount of plastic film rather than in a large disposable plastic jug. Removing the plastic jug creates the false perception that plastic has been removed altogether. Moreover, because PVA is water-soluble, it appears to simply disappear when mixed with water, such as in a washing machine or dishwasher. Out of sight, out of mind.

Unfortunately, being water-soluble does not mean that PVA disappears or changes into non-plastic components when it touches water. Sugar is also water-soluble, but you can taste it after it dissolves in your drink. Dissolved plastic has to go somewhere, and when used in home appliances it goes down the drain and enters the local sewage system, where it eventually arrives at a wastewater treatment plant, or WWTP.

Sewage goes through various levels of treatment, including separating solids from liquid waste and removing contaminants from the wastewater. Once it is considered safely reclaimed, what was once sewage is released into the environment as either liquid effluent (water released after being treated) or solid waste (biosolids).

The released effluent water contains PVA that was not properly or thoroughly processed during treatment. Whether the PVA bypasses the WWTP and is directly released, or is released through effluent, it ends up in the environment in rivers, lakes, and oceans, contributing to plastic pollution. PVA that has not biodegraded completely in the WWTP may be removed with the solids, which are eventually incinerated, sent to the landfill, or reused for agricultural purposes.

Figure 4 below from the PVA study shows the estimated annual usage and emissions of PVA in the United States, measured in metric tons.

Source: Polyvinyl Alcohol in US Wastewater Treatment Plants and Subsequent Nationwide Emission Estimate - Figure 4

Is PVA biodegradable?

The term “biodegradable” means that a material can be fully broken down by living things such as microorganisms. Previous studies have demonstrated that PVA has the potential to biodegrade into simple byproducts (carbon dioxide and water). However, a large amount of the PVA used today does not experience the conditions necessary to do so. This is similar to the argument that plastics are recyclable in theory when in reality only 9% of plastic waste has ever been recycled.

PVA breakdown happens most readily in an environment with specific temperatures, microbes, and other conditions. The typical operations at wastewater treatment plants in the United States do not provide these conditions. While they often do contain bacteria capable of breaking down PVA, the presence of these bacteria is not enough on its own. There needs to be enough bacteria present at the right temperature for the right amount of time.

Other factors, like the concentration of the sludge and the presence of other pollutants, can affect how much PVA is broken down. WWTPs in the United States work based on a priority list of pollutants defined by the EPA. This list is very specific and includes highly toxic items like benzene, lead, and mercury. The treatment plants are designed to remove these priority pollutants, meaning they may not have the ideal conditions for breaking down lower-priority items, including dissolved plastics.

There are two main ways to change this. The first is for the EPA to update its list of priority pollutants and subsequently upgrade wastewater treatment plants to accommodate these substances. This would require most cities to upgrade their water treatment systems. The second approach is to prevent pollutants from entering the water system in the first place.

Several other substances, including pharmaceuticals and cat litter, are not fully removed during wastewater treatment. There have been semi-successful campaigns telling people not to flush drugs or litter down the drain because our wastewater infrastructure is not designed to remove them.

At Meliora Cleaning Products, we believe the same should be true for PVA: we should not intentionally release plastic into our waterways by doing everyday activities like laundry.

Switch to a plastic-free laundry detergent

The best way to prevent plastic from entering the water system through home appliances is to use products without disposable plastic. PVA is a great example of an unfortunate material substitution. These products trade the plastic jug for plastic PVA directly inside the pod or sheet, wrapping each load of laundry detergent in plastic.

At Meliora Cleaning Products, “less plastic” and “plastic in a different form” aren’t good enough, because we know that we can do better. Our entire product line is single-use plastic-free, and most of our products are completely plastic-free. Our Laundry Powder is packaged in a paper and steel canister and comes with a stainless steel scoop. No hidden plastic liner, plastic scoop, or dissolvable plastic pods or sheets inside. When you run out of powder, you can save the can and refill it with low-waste refills.

When we know better, we do better. At Meliora Cleaning Products we will continue our journey of assessing all available ingredients and packaging materials to offer only the best for people and the planet.